A winter's passage has been captured by cameras and instruments measuring ice thickness, salinity, oxygen and phytoplankton abundance in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. These data are being analyzed by staff scientist Akash Sastri and Scientific Data Specialist Alice Olga Victoria Bui, revealing new insights into how conditions evolve beneath the ice over the long Arctic winter. The data are being collected by instrumentation attached to a community observatory operating at a depth of approximately 6 metres below the surface and connected by cable to a nearby wharf for realtime data collection.

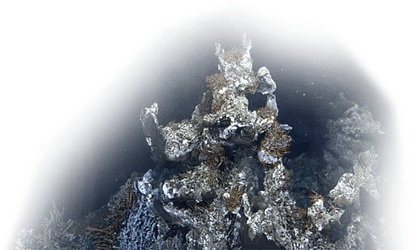

A Greenland cod (Gadus ogac) swims beneath the winter ice in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, 14 February 2014.

The instrument platform hosts an HD video underwater camera and underwater microphone, a suite of sensors to measure seawater properties, plus an instrument to measure ice thickness. On the wharf, a second camera monitors surface ice formation and a small weather station provides information on current meteorological conditions. From the wharf, data are transmitted over a wireless link to a local school, where an Internet connection makes data available beyond Cambridge Bay.

Ice Growth and Retreat

The growth and decline of sea ice in the bay can be tracked in the following plot of ice draft, which is a measure of ice thickness below the sea surface. The plot shows the first annual cycle of sea ice formation and melting recorded by the seafloor-mounted ice profiler in Cambridge Bay during the 2012-2013 winter. Sea ice began forming on 18 October 2012 and built up at a nearly constant rate of 0.87 cm/day throughout winter, reaching a maximum thickness of nearly 2 metres on 25 May 2013. The ice then melted 5 times faster than it formed, retreating completely by 27 June 2013.

Development of ice draft (thickness) during the 2012-2013 winter in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut.

Temporal Salinity Patterns

What happens to the water under the ice as the sea ice forms and thickens? Sea ice formation has a strong impact on salinity, as is shown in the following graph.

Changes in salinity beneath the ice during the 2012-2013 winter in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut.

Sea ice formation begins with spicule-shaped crystals called frazil ice. These crystals, composed of fresh water, do not include sea salts in the freezing process. As a result sea salts are concentrated into droplet called brine and are slowly expelled into the water column below the ice resulting in the observed increase in salinity over the course of the winter. During the melt season, salinity levels start to drop as fresh water is released into the sea from the melting ice layer.

Plankton and Oxygen

Phytoplankton are microscopic plant-like cells that form the base of marine food webs. The growth of phytoplankton and their production of oxygen depends in part on light availability as an energy source. These relationships are illustrated in the following plot of light (orange), phytoplankton biomass (green) and oxygen concentration (blue).

Light amounts, phytoplankton abundance (shown by chlorophyll a concentrations) and oxygen concentrations during the 2012-2013 winter in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut.

During low-light winter conditions, phytoplankton biomass drops to very low levels. The remaining phytoplankton do not produce an appreciable amount of oxygen (blue line) during the winter. Oxygen levels continue to diminish from November 2012 to April 2013 because there is limited gas exchange through the ice with the atmosphere and because of oxygen consumption by marine organisms and organic matter decomposition.

In the late winter, the longer days are accompanied by greater light penetration through the ice, triggering a rapid increase in phytoplankton biomass and dissolved oxygen concentration; this pattern is characteristic of a "bloom." Note that this mini-bloom occurs in early April 2013, long before the onset of ice melting and the seasonal spring phytoplankton bloom. Oxygen concentrations climb steadily after the initial mini-bloom, reaching maximum levels after the completion of ice melt in early July.

Visiting Fish

What were fish doing during the long Arctic winter? At least one was nosing around the underwater observatory. On 14 February 2014, the remotely operated camera recorded this footage of a Greenland cod (Gadus ogac) investigating the community observatory. At this time of year, the sea surface is frozen over, and the bay serves as a transportation corridor for people on snowmobiles. The hydrophone installed on this community observatory recorded the sound of a passing snowmobile just past 5:00 PM local time. As the snowmobile sounds receded, a curious Greenland cod (swam beautifully above a seabed inhabited by numerous Ceriathid anemones.

Resources

Related Story: Cambridge Bay, a Year of Data!

Arctic Sea Ice FAQ