Brett Jameson, University of Victoria PhD student. Photo: UVic Photo Services

December 23, 2020 - Jody Paterson

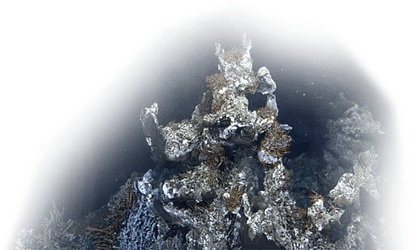

Deep in the ocean off Vancouver Island’s west coast, a gas associated with climate warming is making its way to the surface. Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a product of plankton decomposition, pulled to the surface in areas where deep-sea waters migrate upwards in what’s known as coastal upwelling.

Where is it coming from? That’s a question that University of Victoria PhD student Brett Jameson is exploring, in collaboration with Ocean Networks Canada (ONC), a UVic initiative, and the Canadian Healthy Oceans Network (CHONe).

The world’s oceans both consume and produce gases that affect climate warming, says Jameson of the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. A quarter of the N2O released into the atmosphere comes from the ocean. By pulling up water rich in N2O from the deep, upwelling can transfer deep ocean N2O to the atmosphere.

Jameson’s research, supervised by ONC’s chief scientist Kim Juniper, looks at the production of N2O by microbes in marine sediments, and at the factors that determine whether the gas ends up released to the atmosphere or consumed along the way.

The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development begins next year, with a goal of bringing together stakeholders around the world to find ways to reverse the cycle of decline in ocean health.

ONC and its researchers will be key in that work. ONC continuously delivers and manages real-time data for researchers from its network of cabled observatories, remote control systems and interactive sensors installed along Canada’s three coasts.

ONC has been monitoring low-oxygen waters off Vancouver Island for the past 10 years, and there’s convincing evidence that the oxygen-minimum zone (OMZ) is expanding along with other global OMZs.— Brett Jameson, UVic PhD student

He is referring to the distinct bands of deep water he is studying, known to act as hotspots of N2O production.

Jameson has studied nitrous oxide production in marine sediments in Bermuda and off Vancouver Island’s west coast, where a mid-water OMZ extends from the island to Oregon. He sampled sediments in pristine coastal mangrove forests in Bermuda to compare with results from his deep-sea research.

The two oceans manage nitrous oxide differently. The Atlantic mangrove sediments seem to act as a “sink,” absorbing N2O from the atmosphere. Pacific deep-sea sediments off Vancouver Island release nitrous oxide to the water, and then to the atmosphere.

“These systems are acting very differently— what might be driving this?” asks Jameson. “Are there important differences in the microbes that produce N2O? Or is this variability due solely to environmental factors, such as oxygen concentrations and nutrient levels?”

The notion that pristine mangrove ecosystems may draw in N2O from the atmosphere and consume it will have important implications for conservation and restoration initiatives, he adds.

Most of the growth in N2O concentrations in the atmosphere is a result of human activity. It’s a by-product of agricultural practices, fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes.

But as climate change accelerates the expansion of OMZs, the oceans may account for more of this growth in the future. His research adds to a growing understanding of that vital connection.

EdgeWise

Nitrous oxide isn’t as prominent as carbon dioxide in the public discussion around climate warming, but it has more than 300 times the potency of CO2 as a greenhouse gas.

Oceans are “big and hard to study,” notes Jameson, and his research in the waters off Bermuda and Vancouver Island will need to be followed up in other parts of the world to learn how other ocean environments are managing N2O. “What I hope our research does is stimulate interest in looking at these environments,” he says.

Not one to let a pandemic get in his way, Jameson travelled to Bermuda this past summer as planned to finish his field studies. He co-mentored a UVic student while there, pleased to be “in the cool spot of straddling the line of learning and teaching.” His research is funded by the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences, ONC, CHONe and UVic.

Jameson’s research was recently published in Limnology and Oceanography Letters. Building on this research, the team is developing new methods to investigate processes in marine sediment.

Read the article on UVic News here Read the research paper here