The new enrichment/colonization experiment began in May 2014 at the Barkley Canyon site of the NEPTUNE observatory. Led by Professor Craig Smith of the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Professor Lisa Levin, from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and by ONC staff scientist Fabio De Leo, this deep-sea community sucession experiment uses subsea cameras to observe the changes in the seafloor communities (invertebrates and fish) triggered by the implantation of various organic and inorganic substrates such as whale bones, wood and authigenic carbonate. Whalebones and driftwood form chemosynthetic substrate habitats on the deep seafloor after being decomposed by specialized bacteria, attracting a distinct benthic fauna that resembles communities living in the extreme environments of hydrothermal vents and cold (methane) seeps. This type of experiment also sheds light into how benthic organisms utilize the sparse food resources available in deep-sea settings.

This advanced ocean observatory technology allows researchers to monitor early community colonization and sucessional processes in ways never before possible, at high-frequency and high-resolution. "This is the first time we are able to control our observations in deep water by recording the experiments on a daily basis every two hours and turning on the lights at any time to make further observations." – said Dr. Fabio De Leo, ONC staff scientist.

Previously, those types of experiments could only be monitored by sporadic revisits by ROVs or submersibles, or by autonomous free-vehicles, meaning a lot of the patterns of faunal colonization and succession could not be resolved.

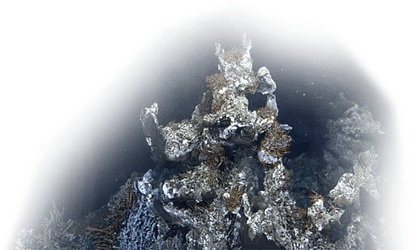

Images from Barkley Canyon POD3 camera (890 m) showing the whalebones, carbonate, and wood block substrates one week after the deployment last May. The INDEEP larval settlement experiment was redeployed and continues to provide important data on deep-sea faunal connectivity.

What's next?

But ‘Bigger is Better’ and Professor Smith and ONC scientists are currently seeking research funds to deploy a whole whale carcass on the seafloor near the ONC cabled observatory infrastructure at Barkley Canyon. This ambitious research project aims to monitor the succession in the benthic community structure following this large pulse of nutrient-rich material with a time resolution never attained before. It is expected that this project will attract additional funding. As a result of engaging with this new research community, ground-breaking scientific discoveries and enormous educational and outreach opportunities continue.

Computer rendering of what a deep-sea whale fall experiment would look like near the ONC observatory node and instrument platforms in Barkley Canyon. Wally the crawler could potentially be used to perform excursions near the whale that would measure chemical signals of the carcass decomposition.

In October 2014, Professor Smith visited Ocean Networks Canada to share his experience and discuss marine operations logistics of the experiment that would involve placing a 40-ton dead whale carcass onto the deep-sea floor with sufficient precision to benefit from the already installed sensors, and carefully enough not to damage any of the seafloor infrastructure. Professor Smith has sunk many dead whales in water depths ranging from 30 to 3,000 meters at various locations in oceans around the world.

Why place Whale Bones on the Seafloor?

by Fabio De Leo, May 14, 2014

Originally posted on Wiring the Abyss 2014 Expedition portal.

This year, Ocean Networks Canada is launching a series of new deep-sea scientific experiments on NEPTUNE observatory. One such experiment, a collaboration with the International network for Scientific investigation of deep-sea ecosystems (INDEEP), is the deployment of whale bones at nearly 900 m depth in Barkley Canyon site, in front of the POD3 camera.

The bones (3 rib sections) are from a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeanglia) that stranded on the Alaskan coast, sometime around May 2007

Dr. Craig Smith, a researcher at the University of Hawaii, Manoa, processes humpback whale bones, removing flesh and sinew. These bones were prepared for deployment in Barkley Canyon as part of a deep-sea experiment.

University of Hawai’i’ professor Craig Smith, the scientific lead for this experiment, has deployed packaged bones from this same whale off the coasts of Newport, Oregon and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, as part of a research project funded by U.S. National Science Foundation. Craig and colleagues are studying the remarkable animals that colonize whale bones, at different depths and in different ocean basins.

Whale bones lay arranged on the ground after initial preparations by Dr. Craig Smith of the University of Hawaii, Manoa, April 2014. These bones were prepared for deployment to Barkley Canyon as part of a deep-sea experiment.

But why should we care about whale bones on the seafloor in the first place? In the late 1980’s Craig and his colleagues accidentally discovered a whale carcass during a dive with the submersible Alvin, at 1240 m off the coast of Santa Catalina, California. What was exciting about this discovery was the finding that the whale skeleton harboured a very rich and unique community of organisms, some of which were new to science. Craig subsequently dedicated part of his academic career to studying the novel seafloor oasis ecosystems formed by sunken whale carcasses. (See Ecology of whale falls at the deep-sea floor.)

Footage of the decomposition of a large whale carcass in the deep sea. Notice the successional changes in the community that is supported by this massive input of nutrients. This video is produced by the laboratory of Dr. Craig Smith, University of Hawaii.

Dr. Smith and his colleagues have postulated that whale falls are very important energy sources for the deep sea, which is otherwise a very food-limited environment. When a large (many tonnes) carcass first arrives on the seafloor, it provides the benthic communities with a rare feast. Even more interesting was their discovery that long after the flesh is gone from the whale carcass, these oasis communities are sustained, sometimes for decades, by the decomposition of lipids contained within the bones. They have even postulated that whale carcasses can serve as stepping-stones for the dispersal of hydrothermal vent and cold seep faunas.

Fabio holds humpback whale bones for deployment at Barkley Canyon—part of a new experiment led by Craig Smith.