NEWS RELEASE

In a scary movie, creatures that can’t always be seen often provide the biggest frights for characters and viewers alike.

In deep-ocean research, the absence of one particular creature—the so-called zombie worm, “the bone devourer” Osedax—can also be troubling, a harbinger of species loss and ecosystem decline due to the long-term effects of climate change.

Fabio De Leo, a senior staff scientist with Ocean Networks Canada (ONC) and adjunct assistant professor with the University of Victoria’s (UVic) Department of Biology, co-led an experiment that studied humpback whale bones placed on the deep ocean floor off the British Columbia (BC) coast, and found no evidence of the zombie worm that plays a critical role in bone decomposition.

While it has no mouth, anus or digestive tract, Osedax—known as an ecosystem engineer species—has roots that bore into the bones and microbes that extract nutrients to feed the worms.

The fact that ONC’s high-resolution underwater cameras didn’t detect zombie worm colonization on the bones over 10 years of observation—what’s called a negative result in scientific research—is notable and troubling, says De Leo.

“This was a remarkable observation in such a long-term experiment,” he says, noting it may be explained by the low concentrations of oxygen present at the observation site.

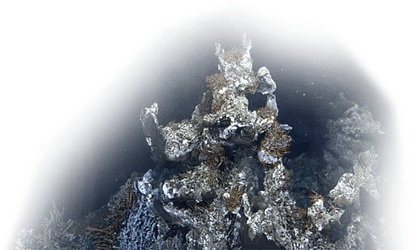

Barkley Canyon, where the whale bones were placed almost a thousand metres below the sea surface of the Pacific Ocean, is in a naturally occurring low-oxygen zone located on the migration routes of humpback and grey whales. Whales that die from natural causes or human threats like ship strikes or fishing nets often sink to the seafloor, creating “whale falls” that provide a bonanza of food to support new biodiversity hotspots. But the absence of zombie worms on these bones suggests that expanding oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) in the northeast Pacific and elsewhere, driven by climate change, might disrupt these ecosystems more broadly.

Furthermore, preliminary data from pending whale fall research near a different ONC NEPTUNE site suggests that zombie worms may be affected elsewhere too.

Why we need bone devourers

If the “bone devourer” isn’t there to carry out its tasks and promote the succession process around the whale, other species may be unable to colonize and further utilize whale-carcass nutrients. Whale falls are “almost like islands,” De Leo says, “and a stepping-stone habitat for this and many other whale bone specialist species.”

“Basically, we're talking about potential species loss,” he says, explaining that the adult Osedax generally grow on whale bones and their larvae are dispersed large distances in the ocean to populate other whale fall ecosystems even hundreds of kilometers away. “So, this connectivity, these island habitats, will not be connected anymore, and then you could start losing a diversity of Osedax species across regional spatial scales.”

Furthermore, the researchers found that another ecosystem engineer, wood-boring Xylophaga bivalves, also appears affected by low-oxygen stress. While these bivalves were seen on the experiment’s submerged wood samples at Barkley Canyon, they colonized at much lower rates than more oxygenated ocean areas, with implications for slowed carbon decomposition and colonization by the many species typically inhabiting Xylophaga burrows.

“It looks like the OMZ expansion, which is a consequence of ocean warming, will be bad news for these amazing whale-fall and wood-fall ecosystems along the northeast Pacific Margin,” said Craig Smith, professor emeritus from University of Hawaii, who co-led the experiment.

De Leo and Smith used ONC’s NEPTUNE observatory Barkley Canyon Mid-East video camera platform and oceanographic sensors, as well as high-definition video surveys from remotely operated vehicle surveys, to collect the environmental data. In the coming months, they will release additional research findings about a whale fall being monitored at NEPTUNE’s Clayoquot Slope site.

Watch this video to learn more.

This research was supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation Major Science Initiative Fund and in part by a US National Science Foundation grant. It aligns with United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14, life below water.

Ocean Networks Canada (ONC) operates world-leading observatories in the deep ocean and coastal waters of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic coasts of Canada as well as the Southern Ocean, collecting ocean data that accelerates scientific discovery and makes possible services and solutions for a resilient planet. ONC’s cabled observatories supply continuous power and Internet connectivity to scientific instruments, cameras, and 12,000-plus ocean sensors. ONC also operates mobile and land-based assets, including coastal radar. ONC is an initiative of the University of Victoria and is one of Canada’s Major Research Facilities.

A media kit containing photos and video is available.

-- 30 --

Media contacts:

Robyn Meyer (ONC Communications) at 250-588-4053 or rmeyer@uvic.ca

Jennifer Kwan (University Communications and Marketing) at uvicnews@uvic.ca

About the University of Victoria

The University of Victoria is a leading research-intensive institution, offering transformative, hands-on learning opportunities to more than 22,000 students on the beautiful coast of British Columbia. As a hub of groundbreaking research, UVic faculty, staff and students are making a significant impact on issues addressing challenges that matter to people, places and the planet. UVic consistently publishes a higher proportion of research based on international collaborations than any other university in North America. Our commitment to advancing climate action, addressing social determinants of health, and supporting Indigenous reconciliation and revitalization is making a difference—from scientific and business breakthroughs to cultural and creative achievements. Find out more at uvic.ca. Territory acknowledgement