A native of Quebec City, Julie-Anne Dorval is a 24-year old oceanography Master’s student from the Institut des sciences de la mer de Rimouski at the University of Quebec. For Julie-Anne, her undergraduate studies in marine biology and a technical degree in bioecology are a natural progression of a childhood fascination with sea life. Today, her research focuses on the ecology of marine invertebrates in the Canadian Arctic using video and samples from ONC’s ocean observatory at Cambridge Bay. Julie-Anne’s supervisors are Philippe Archambault at Rimouski and Kim Juniper, Chief Scientist at Ocean Networks Canada.

Marine biologist Julie-Anne Dorval displays an Arctic nudibranch (sea slug) Dendronotus sp (unconfirmed) from the shallow waters of Cambridge Bay. September 2014.

What inspired you to choose your path in ocean science?

As far back as I can remember, I’ve loved the ocean. My parents used to bring me to the beach where I played and tried to “classify” marine animals. I also had a whole collection of shells at home. When I was about six years old, I saw a TV documentary about belugas and told my parents that I wanted to become a biologist. Since then, I’ve never deviated from that path. The oceanography and invertebrate courses during my technical and undergraduate years have solidified my desire to pursue a career as an oceanographer.

How did you become familiar with the observatories and data at Ocean Networks Canada?

For a summer project during my undergraduate studies, I worked with ONC underwater videos from Cambridge Bay. My supervisor told me it could be interesting to do a more in-depth analysis of this material. When I finished my undergraduate degree, I decided to transform that summer project into a Master’s project. I’ve always wanted to work in the Arctic and this was a perfect opportunity to work at the Cambridge Bay observatory with the ONC expedition team in September 2014.

Any favourite expedition stories?

My most memorable one from Cambridge Bay was the formaldehyde that took almost eight months to be delivered by airplane. I needed the formaldehyde to preserve my samples of the Cambridge Bay invertebrates. Of course, I needed it right away! It was a stressful search, but we managed to find some formaldehyde on the Coast Guard icebreaker Laurier, that was doing a port call in Cambridge Bay, and my samples were saved!

Do you have a particular animal you’ve become fond of?

Nudibranch, nudibranch, nudibranch! These sea slugs are amazing creatures. We have a wonderful picture of a nudibranch in Cambridge Bay.

Can you tell us what you hope to understand through your research?

My first objective in this study is to measure the abundance and diversity of marine invertebrates that live on and in the seabed, and to compare this between seasons and years so that we can have a baseline to understand climate change effects. This research is possible because of Ocean Networks Canada’s cabled seafloor observatory in Cambridge Bay that captures realtime video over long periods of time.

My second objective is to get a better understanding of the link between the organisms that live on the seabed and in the seabed (in the mud), and how they affect each other. This type of study is called “patch dynamics.” We performed a small scale (200 m) survey near the observatory where we took mud samples, videos and pictures to analyze the “patch dynamics”.

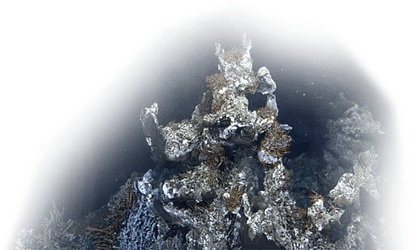

While this video still frame may not look impressive at first glance, this microscale seafloor survey, or transect, is an effective tool to further scientific analysis of life in the Arctic ocean and its interactions.

How have the data and infrastructure from Ocean Networks Canada assisted your research?

The ONC team helped me so much during my field work. They made it possible to get my mud samples and my transect in Cambridge Bay last year. I think the Cambridge Bay observatory is a crucial tool for gathering data from the Canadian Arctic, and makes research projects like mine possible. Year round data are precious in the Arctic, since the weather is challenging and research resources are limited. Thanks to ONC for the innovative tools that help us gather new data.

Julie-Anne takes grab samples of Cambridge Bay mud for later study in the lab.

What is keeping you busy today?

Now, I am busy with my second objective, which is analyzing the video of the transect. This includes annotating the many different species, their abundances, the presence of trash on the sea bed, and also perturbation or bioturbation, which are changes caused by outside influences, and the mixing of sediments by moving animals or plants. This analysis will help me better understand the “patch dynamics” of the organisms living on the seabed.

Any plans for the future you’d like to share?

Working with video from the cabled observatory as a research tool is really interesting. It’s a new type of data that can provide crucial information, especially in the Arctic. I hope I can specialize in this domain and continue researching with underwater video after I graduate.

Learn more about the Cambridge Bay Observatory:

- Expanding the Cambridge Bay Observatory (2015)

- the Arctic community observatory at Cambridge Bay (for daily data plots including CTD, weather station, ice profiler and daily time lapse)

- Greenland cod at Cambridge Bay (video)